Janneke de Kort was well on her way to become a brilliant psychological scientist when during her PhD she fell ill with an aggressive form of leukemia, a little later in May of 2016 died. Because it takes time for people to get their scientific work out into the world, time she did not have, her brilliance was primarily recognized by those that worked with her, or alongside her. But make no mistake she was brilliant. She was brilliant and knew it, but didn’t let that get in her way. She was self-critical, hard on herself and others, kicked up, never down, here academic work was rigorous, formal, intense and tenacious. Janneke had chosen a career in psychological sciences after working in psychiatric care and finding herself utterly dissatisfied with the practice. Her very few published works are illuminating and are relevant for the public discourse on individual difference in cognitive ability and psychopathology, they are however overlooked as she is no longer here herself to champion and further them.

Janneke made vital contributions via three papers that were part of a broader intellectual effort spun from the mind of Professor Conor Dolan, the source of which can be traced back to the beginning of his 30 year collaboration with Prof Dorret Boomsma in the early 1990’s and late 1980’s. First Conor, during her masters in the psychology reseach master’s program at the UvA, and later Dorret, at the VU during het PhD, worked closely with Janneke. Here work, published during her Master’s at the UvA in 2012 and during her PhD in 2014 was ahead of its time and pertains to the role genes and the environment play in the developmental process which gives rise to individual differences in cognitive traits (Intelligence, personality) and psychopathology. Janneke worked on, and offered an empirical solution to, questions that where on the minds of legends in the fields.

There is intuitive evidence consistent with the fact that adult individual differences in IQ, personality and psychopathology are heritable. This doesn’t mean these traits are set in stone, or set in the chemical bonds that form out DNA, it only means that within a homogenous population (REALLY hard to define…) individual differences in genotype correlate with individual differences in phenotypes. The most intuitive evidence comes from twin studies where for a trait the correlation between monozygotic twins, which share all their DNA, are contrasted with the correlation between dizygotic twins, who share half the variable sites in their DNA. If a trait is highly correlated for both mono and dizygotic twins, this is solid evidence that the similarities are attributable to the shared childhood or even pre-natal environment. However, if monozygotic twins are more alike the than the dizygotic twins that is consistent with individual differences in a trait being the consequence of heritable difference. For a trait like IQ, a metric intended to measure intelligence, the heritability starts out modest early in childhood by early adult hood it is ~60%, a statistic that is often take wildly out of context and offered as an inescapable fact with wide societal ramification. The logic of a twin model seems solid, and the results of heritability studies in adults do seem to point to genetic causes on individual differences. However, implicitly it is assumed the environmental influences and the genetic influences are uncorrelated. This assumption which is universally acknowledged to be an unrealistic by people in the field who otherwise agree on very little. To just look at the outcome in adults is to overlook the developmental process and to willfully stay ignorant of the role of development, parents and society.

There is a long literature trying to explicate, formalize and expose the role of development in gene-environment correlation, there is work by Dickens and Flynn which tries formalize how seeking out compatible environments based on heritable traits in early childhood (I am good in sports so I train more and seek out new challenges) could correlate genes to the environment, there is work by others like Eric Turkheimer modeling the role developmental dynamics and there is work by Lyndon Eaves dating back to 1977 that formally distinguished three sources of gene environment correlation, niche picking, sibling effects and cultural transmission where parents shape (or are unable too due to societal constraint) the rearing environment of their child. It good to keep in mind that the label “niche picking” suggests a process entirely driven by the free will of a child, but children can be coached guided or backed into a niche by parents, teachers or society. Many others have commented on, suggested, probed and questioned the nature on gene environment correlation, and I cannot possibly do them all justice here, as I wish to return to Janneke.

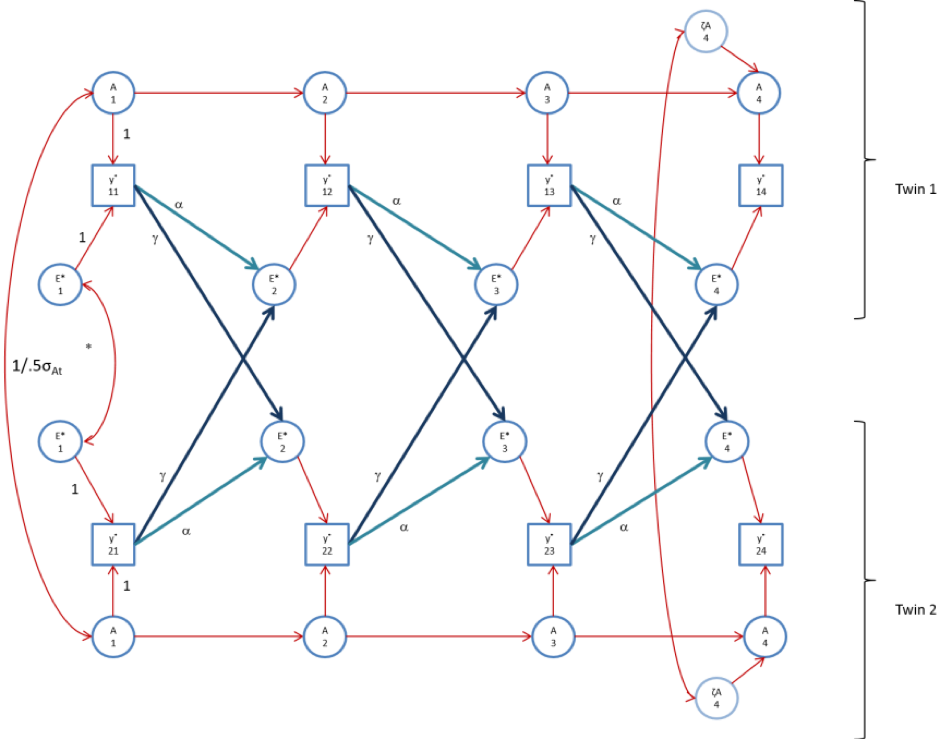

Janneke, as a masters student, patiently supervised by Conor Dolan, developed a model that could jointly estimate two of these sources of gene environment covariance: niche picking, selecting or being selected into environments based on your current ability, and sibling effects, contributing to a facilitating environment for your sibling. Their model is quite the beast, but indulge me and let me talk you trough it:

You see 8 squares which reflect, from left to right IQ measured at ages 5, 7,10 and 12 in Dutch twins where each row reflects the time series for a single twin. If we focus exclusively on the top left square, IQ at age 5 in twin 1 (labeled y11). We see that two circles have an arrow going into this observation, the genetic (A1), and environmental (E2) effect, the genetic effect is correlated with the genetic effect on the other twin, and the correlation is known to be 1 or 0.5 for the mono- and di-zygotic twins, the environmental effect is also (freely) correlated between the twins. The genetic effects (A1) at time t-1 have an arrow going into the genetic effects at time t (A2), the same genes play a role later, the same holds for the environmental effects (E1 -> E2). What is special about this model is that the phenotype at the first timepoint (top left…) has blue arrows going into the environment of the phenotype at a later age as well as the environment of the twin, the blue shades reflect the different niche picking (alpha) and sibling effects (gamma). Now developing a model like this involves more then just adding an arrow to an existing model, it involved a healthy dose of mathematical statistics, a grinding process of evaluation of each parameter and under which conditions one can estimate it. Few people have the ability and tenacity to see it through, Janneke did. Janneke went on to apply this model to IQ measured in Dutch twins measured repeatedly between the ages of 5 and 12 show that while in the standard model (no blue arrows) the heritability of IQ is ~ 55% at age 12 or early adolescence while in the equally well-fitting model she developed which allowed for niche picking and sibling effects the direct effect of genes is far more modest (21%) with a big contribution attributable to dynamic indirect genetic effects induced by gene-environment correlation (33%). Both models fit the Dutch data equally well, her findings where replicated within a year by Beam et al. who independently arrived at a very similar model and conclusion. Her model has profound implications in that if the environment is improved (better schooling better access to remedial teaching etc.) the increase in IQ induced by the environmental change is supercharged by the gene-environment correlation and the process ensures that despite the change/improvement in environment the trait remains heritable. These processes are subtle and intricate mechanisms in human development and those that work on these problems today find their work in high demand, I often wonder how their work and understanding would have been influenced, and I believe improved, by Janneke.

Since her death others have popularized molecular genetic analysis of other sources of gene environment correlation with as a highlight a brilliant Science article on the nature of nurture Kong et al. I have no doubt Janneke would have thrived in modern day behavior genetics and psychological science where gene-environment correlation and development are increasingly viewed as central to the etiology of behavior, psychopathology and cognition.

Janneke Bibliography:

De Kort, J. M., Dolan, C. V., Kan, K. J., Van Beijsterveldt, C. E., Bartels, M., & Boomsma, D. I. (2014). Can GE-covariance originating in phenotype to environment transmission account for the Flynn effect?. Journal of Intelligence, 2(3), 82-105.

Dolan, C. V., de Kort, J. M., van Beijsterveldt, T. C., Bartels, M., & Boomsma, D. I. (2014). GE covariance through phenotype to environment transmission: an assessment in longitudinal twin data and application to childhood anxiety. Behavior genetics, 44(3), 240-253.

de Kort J. M., Dolan C. V., Boomsma D. I. (2012). Accommodation of genotype–environment covariance in a longitudinal twin design. Neth J Psychol, 67(3):81–90